Knowledge is power. When children understand what’s happening in the brain, it can be the first step to having the power to make choices. Knowledge can be equally powerful to parents too. Knowing how the brain works means we can also understand how to respond when our children need our help.

Sometimes our brains can become overwhelmed with feelings of fear, sadness or anger, and when this happens, it’s confusing – especially to children. So giving children ways to make sense of what’s happening in their brain is important. It’s also helpful for children to have a vocabulary for their emotional experiences that others can understand. Think of it like a foreign language; if the other people in your family speak that language too, then it’s easier to communicate with them.

So how do you start these conversations with your children, make it playful enough to keep them engaged, and simple enough for them to understand?

Here is how I teach children (and parents) how to understand the brain.

Introducing the brain house: the upstairs and the downstairs

I tell children that their brains are like a house, with an upstairs and a downstairs. This idea comes from Dr Dan Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson’s book ‘The Whole Brain Child’, and it’s a really simple way to help kids to think about what’s going on inside their head. I’ve taken this analogy one step further by talking about who lives in the house. I tell them stories about the characters who live upstairs, and the ones who live downstairs. Really, what I’m talking about are the functions of the neocortex (our thinking brain – the upstairs), and the limbic system (our feeling brain – the downstairs).

Who lives upstairs and who lives downstairs.

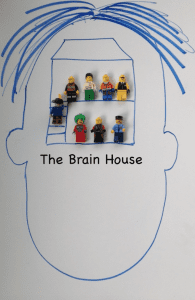

‘The Brain House’

Typically, the upstairs characters are thinkers, problem solvers, planners, emotion regulators, creatives, flexible and empathic types. I give them names like Calming Carl, Problem Solving Pete, Creative Craig and Flexible Felix

The downstairs folk are the feelers. They are very focused on keeping us safe and making sure our needs are met. Our instinct for survival originates here. These characters look out for danger, sound the alarm and make sure we are ready to fight, run or hide when we are faced with a threat. Downstairs we’ve got characters like Alerting Allie, Frightened Fred, and Big Boss Bootsy.

It doesn’t really matter what you call them, as long as you and your child know who (and what) you are talking about. You could have a go at coming up with your own names: try boys/girls names, animal names, cartoon names or completely make-up names. You might like to find characters from films or books they love, to find your unique shared language for these brain functions.

Flipping our lids: When ‘downstairs’ takes over.

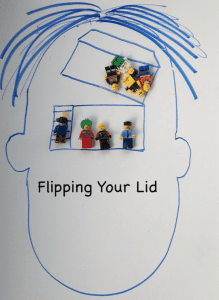

‘The Brain House: Flipping Your Lid’

Our brains work best when the upstairs and the downstairs work together. Imagine that the stairs connecting upstairs and downstairs are very busy with characters carrying messages up and down to each other. This is what helps us make good choices, make friends and get along with other people, come up with exciting games to play, calm ourselves down and get ourselves out of sticky situations.

Sometimes, in the downstairs brain, Alerting Allie spots some danger, Frightened Fred panics and before we know where we are, Big Boss Bootsy has sounded the alarm telling your body to be prepared for danger. Big Boss Bootsy is a bossy fellow, and he shouts ‘the downstairs brain is taking over now. Upstairs gang can work properly again when we are out of danger’. The downstairs brain “flips the lid” (to borrow Dan Siegel’s phrase) on the upstairs brain. This means that the stairs that normally allow the upstairs and downstairs to work together are no longer connected.

Sometimes, flipping our lids is the safest thing to do.

When everybody in the brain house is making noise, it’s hard for anyone to be heard. Bootsy is keeping the upstairs brain quiet so the downstairs folk can get our body ready for the danger. Boots can signal other parts of our body that need to switch on (or off). He can make our heart beat faster so we are ready to run very fast, or our muscles ready to fight as hard as we can. He can also tell parts of our body to stay very very still so we can hide from the danger. Bootsy is doing this to keep us safe.

Try asking your child to imagine when these reactions would be safest. I often try to use examples that wouldn’t actually happen (again so that children can imagine these ideas in a playful way without becoming too frightened by them). For example, what would your downstairs brain do if you met a dinosaur in the playground?

Everyone flips their lids.

Think of some examples to share with your child about how we can all flip our lids. Choose examples that aren’t too stressful because if you make your kids feel too anxious they may flip their lids then and there!

Here’s an example I might use: Remember when Mummy couldn’t find the car keys and we were already late for school. Remember how I kept looking in the same place over and over again. That’s because the downstairs brain had taken over, I had flipped my lid and the upstairs, thinking part of my brain, wasn’t working properly.

When the downstairs brain gets it wrong.

There might be times when we flips our lids but really we still need the upstairs gang like Problem Solving Pete, and Calming Carl to help us.

We all flip our lids, but often children flip their lids more than adults. In children’s brains, Big Boss Bootsy can get a bit over excited and press the panic button to trigger meltdowns and tantrums over very small things and that’s because the upstairs part of your child’s brain is still being built. In fact, it won’t be finished being built until the mid twenties. Sometimes, when I want to emphasise this point, I ask kids this question:

Have you ever seen your Dad or Mum lay on the floor in the supermarket screaming that they want chocolate buttons?

They often giggle, and giggling is good because it means it’s still playful, so they are still engaged and learning. I tell them parents actually like chocolate just as much as children, but adults have practiced getting Calming Carl and Problem Solving Pete to work with Big Boss Bootsy and can (sometimes) stop him from sounding the danger alarm when he doesn’t need to. It does take practice and I remind children that their brains are still building and learning from experience.

From a shared language to emotional regulation

Once you’ve got all the characters in the brain house, you have a shared language that you can use to help your child learn how to regulate (manage) their emotions. For example, ‘it looks like Big Boss Bootsy might be getting ready to sound the alarm, how about seeing if Calming Carl can send a message saying ‘take some deep breaths’ ’’ .

The language of the brain house also allows kids to talk more freely about their own mistakes, it’s non judgemental, playful and can be talked about as being separate (psychologists also call this ‘externalised’) from them. Imagine how hard it might be to say ‘I hit Jenny today at school’ versus ‘Big Boss Bootsy really flipped the lid today’. When I say this to parents, some worry that I’m giving children a ‘get out clause’ – ‘can’t they just blame Bootsy for their misbehaviour?’. Ultimately what this is about is enabling children to learn functional ways to manage big feelings, and some of that will happen from conversations about the things that went wrong. If children feel able to talk about their mistakes with you, then you have an opportunity to join your upstairs brain folk with theirs, and problem solve together. It doesn’t mean they escape consequences or shirk responsibility. It means you can ask questions like ‘do you think there is anything you could do to help Bootsy keep the lid on?’.

Knowing about the brain house also helps parents to think about how to respond when their child is flooded with fear, anger or sadness. Have you ever told you child to ‘calm down’ when they have flipped their lid? I have. Yet what we know about the brain house is Calming Carl lives upstairs and when Bootsy’s flipped the lid, Calming Carl can’t do much to help until the lid is back on. Your child may have gone beyond the point where they can help themselves to calm down. Sometimes, parents (teachers or carers) have to help kids to get their lids back on, and we can do this with empathy, patience and often taking a great deal of deep breaths ourselves!

Where to go from here?

Don’t expect to move all the characters into the brain house and unpack on the same day; moving house takes time, and so does learning about brains. Start the conversation and revisit it. You might want to find creative ways to explore the brain house with your child. Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- draw the brain house and all the characters

- draw a picture of what it looks like in the house when the downstairs flips their lid

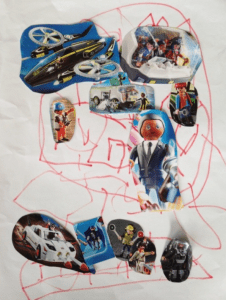

- find a comic, cut out and stick characters into the downstairs and the upstairs

- write stories about the adventures of the characters in the brain house

- use a doll’s house (or if you don’t have a dolls house, two shoe boxes, one on top of the other works just as well) and fill it with the downstairs and upstairs characters.

‘The Brain House’ by Sophie, Age 8

‘The Brain House’ by Jacob, Age 5

If you find other creative ways to explore the brain house, I would love to hear about them. Make it fun, make it lively and kids won’t even realise they are learning the foundations of emotional intelligence.

About the Author: Dr Hazel Harrison

Dr Hazel Harrison works as a clinical psychologist in the United Kingdom. She founded ThinkAvellana to bring psychology out of the clinic and into everyday life. Her website is www.thinkavellana.com and you can also follow her on Twitter at @thinkavellana and on Facebook at www.facebook.com/thinkavellana

Love this article, I am a newly qualified social worker and I think this is a fantastically creative way of helping children and young people as well as their carers, to all understand how their brain impacts on their behaviour and ways to describe it and make sense of it! Thank you. I wil definitely be sharing this with colleagues and the familes I support.

I have been doing research on this for the last 8 years. This year is my culmination year. I adopted a self regulation curriculum for my school district from keri counselor. I am using her resource with grades 3-6. I have also adopted the Zones Regulation Curriculum that I am using with K-2 grades. This is my last year though. I am retiring at the end of the 2020 school year. I hope what I have tried to do in school counseling lessons for my school district has made a difference.

It is great resource for teachers and special education resource. i would like to have more information regarding this them.