Daunted. Overwhelmed. Petrified. That’s how many children feel when faced with the prospect of trying something new where there is so much room to fail.

Whether it’s tasting a new food, diving into a pool or entering a classroom for the first time, they feel paralysed by the risk of not being the best.

And it’s no wonder. As parents, educators and caregivers, many of us were brought up with the mindset that mistakes were something to be avoided, and creativity was an afterthought to perfectionism.

Mistakes are where the magic happens.

But mistakes are an essential part of learning for everyone – they push adults and children alike out of our comfort zones and show us that ‘stuffing up’ is both inevitable and ok. In order to transform that message and navigate a healthy growth mindset for children, we need to invest in a more colourful emotional wardrobe – one that celebrates a day that has difficult moments.

Just like a healthy plate of food that contains many colours, a healthy day should be filled with a range of emotions and experiences.

As a new school year approaches, let’s think about this within the framework of ‘school readiness’. That term itself, ‘school readiness’, no longer seems accurate. What are children even supposed to be ‘ready’ for? As parents and educators, it feels more helpful to focus on the transition to school and the necessary emotional tools to thrive in this next stage. It is no longer about ‘pincer grip’ and being able to write your name in perfect print. Rather, an important part of school transitioning and how well a child will do, can be determined by how interested they are in what they don’t know rather than being scared by it.

The 3 key capacities to support holistic development.

As children transition to school, we are aiming for holistic development where emotional, social and cognitive development is level and integrated. There are three key capacities that we should focus on to support this state:

- The capacity to self-regulate.

- The capacity for ambivalence.

- The capacity to collaborate.

1. The capacity to self-regulate

A child’s ability to self-regulate is perhaps the most important tool for managing transitions and getting through the school day. This is the ability to have an internal modulator that knows how to land and settle. When children have this internal thermostat, they are able to use their energy to learn rather than using it to hold themselves together.

Internal modulation comes from incidental, ordinary transitions. Children develop this skill by feeling properly engaged with and enjoyed, in an ordered and thoughtful way, in ordinary moments throughout the day. It is not about doing new things. It is about making ordinary moments extraordinary and engaging with our children in a settled, focused manner.

Children pick up on our own restlessness. If we are perpetually doing 10 things at once, we can’t be surprised when they then struggle to settle and land. We need to have downloaded our own internal modulator for our kids to do the same. As we know, children need to feel connected with before they can be directed.

You can help children develop an internal thermostat by:

-

-

-

- Turning off phones and screens during dinner and bath time. Sit down to eat as a family. The way we take in food and interact at the dinner table can model for children the ‘deliciousness’ of great learning in the classroom.

- Practising the idea that the quickest way to do something is slowly. Having outside order – e.g. a regular routine of dinner, bath, story, cuddle, bed – facilitates inside order.

- Creating moments for your children to feel properly enjoyed. This will equip them to enjoy the world and others, which is a very important part of starting school.

-

-

2. The capacity for ambivalence

Another predictor of a child’s ability to thrive at school is their capacity for ambivalence – this is the ability to manage things they don’t like as well as the things they do like. The school day will be filled with moments they enjoy and moments they won’t. And their ability to distinguish between needs and wants is imperative to being able to manage the ordinary mess of the classroom that won’t just include pinks and yellows, but also blues and browns and blacks.

To help them distinguish between needs and wants, we should focus on attending to children’s needs, but not their wants as readily. In this way, we can help children have a very clear idea that wants are not needs.

Other ways to help children develop a capacity for ambivalence include:

-

-

-

- Sharing our own days and highlighting that our days too are multi-coloured and filled with new experiences and things we don’t like.

- Supporting them in understanding that new experiences can be scary, and that’s ok.

- Celebrate them for trying new things with interested eyes, rather than aiming for perfection with critical eyes.

-

-

3. The capacity to collaborate

Finally, the capacity to collaborate and ask for help without shame is imperative to the learning experience at school.

The new curriculum highlights the importance of group work over rote learning at individual desks. This is both reflective of, and compatible with, the changing world around us. Computers have taken the jobs of rote learners and it is estimated that 85% of the jobs of 2030 haven’t been invented yet. This means that the deeply ‘human’ qualities of collaboration and creativity are now central to the school experience.

We can support children in developing these skills by:

-

-

-

- Allowing them to witness you asking for help and solving everyday problems as a team.

- Using your family table as a practice classroom table by making it a place of collaboration, listening, reflection and having fun.

- Modelling ordinary conflict moments, turn-taking skills and cooperation.

-

-

As we begin to prepare children for their transition to school and facilitate holistic development, our parting message should be that they will make glorious, magical and amazing mistakes – mistakes that nobody has ever made before.

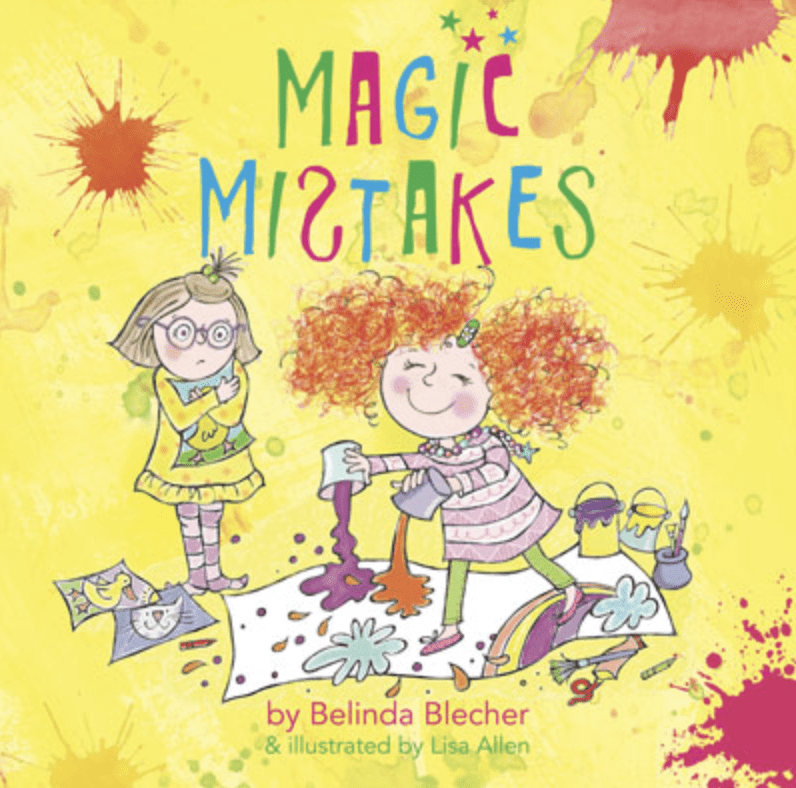

To support children in building resilience and taking safe risks, Belinda has written a fabulous book, Magic Mistakes. As Belinda explains, ‘The idea for writing it came from the high levels of anxiety I have been seeing in children leading up to starting school, particularly around perfectionism. My aim was to take the provision of emotional support out of the clinical setting and create an accessible tool for parents, caregivers and educators to help children name and reframe their everyday, ordinary anxieties.’

About Belinda Blecher

Belinda Blecher trained as a Child and Adolescent Psychotherapist at the Tavistock Clinic, London. In London, Belinda worked at the Royal Free Teaching Hospital for 8 years in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department. After arriving in Sydney in 2004, Belinda worked both at Sydney Children’s Hospital and as the senior clinician at the Early Intervention Program of the Benevolent Society.

Belinda currently runs a preschool consultancy service for early years educators, as well as a private child and adolescent psychology practice.

Belinda has lectured at the Institute of Psychiatry in Sydney and has run seminars for mental health professionals in numerous cities around Australia on working clinically with children under 5 years old.

It’s wonderful that you are getting thoughts from this post as well as from our discussion made at this place.

Great article! Thank you! I’ll read this book for sure!